Exhibition Insight... Materials Matter: A Bauhaus Legacy

Susan Frost, Porcelain vessels, 2017-2019. Photo by Michael Haines.

An interdisciplinary and experimental workshop of ideas.

Words by Rebecca Freezer.

Rebecca is Assistant Curator is JamFactory.

The Bauhaus – it represents an idea, an aesthetic, a moment, a movement, a vision of the future. It conjures up such iconic objects of modern design as a Marianne Brandt Tea Infuser, 1924 or Marcel Breuer’s tubular-steel and leather Wassily chair, 1925. The Wilhelm Wagenfeld table lamp is named simply The Bauhaus Lamp, 1924. It was a community of artists and designers and the most influential modernist art school of the 20th century.

In 2019, in the centenary of its founding, the impact of the Bauhaus is being celebrated around the world. Its international influence extends to the thriving art, craft and design culture in South Australia. The Bauhaus has provided a significant model for JamFactory since its inception in 1973. Not only in its innovative design and fabrication processes, but also in the exhibition and sale of its art and objects. Exhibitors with an affiliation, both past and present, with JamFactory are displayed in Materials Matter: A Bauhaus Legacy. They are: Frank Bauer, Gabriella Bisetto, Lilly Buttrose, Liam Fleming Susan Frost, Christian Hall, Ebony Heidenreich, Kay Lawrence, Jake Rollins and Lex Stobie.

SHARED HISTORIES

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany. Johannes Itten a Bauhaus Master from 1919-1923, taught visual analysis, material study and colour theory as part of the mandatory Vorkurs (preliminary course). The investigations and experiments in materials, colour and form taught in visual arts and design preliminary courses to this day began at the Bauhaus and represent one of its most well-known legacies.

Gropius also revolutionised art and design education by simultaneously developing artistic ideas and technical skills. Two masters were placed in charge of each of the workshops, a ‘form master’ and a ‘technical master.’ The Bauhaus then offered training in a dedicated craft, which focused on a specific material – metal, wood, clay, glass, stone, and textiles, and students traversed study and application of their skills from apprentice to journeyman to master.

Published by Gropius in 1923, the second inner circle of the Bauhaus pedagogical diagram illustrates their interrelationship. JamFactory’s focus on materiality is a salient link to the Bauhaus, which also adopts a masters and apprentice style of peer-to-peer teaching to emerging art and craft practitioners. Historically JamFactory’s craft disciplines have spanned jewellery and metal, furniture, glass, ceramics and textiles.

From 1923-1928, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy superseded Itten as the director of the preliminary course at the Bauhaus. It was during this period that it forged links with industry and fulfilled its pledge to provide well-designed everyday goods for ordinary people. Maholy-Nagy advanced the view that applied art, modern design and industry should and could achieve a mutually beneficial creative nexus. The more money the school could earn through the sale of its workshop products, the less dependent it had to be on funding from the government of the German state of Thuringia. Similarly, there is a link to JamFactory’s decreasing dependence of government funding through its economic activity through its design commissions and production of small batch objects sold through its stores and wholesale nationally.

Under political and financial pressure, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1925. Gropius designed the new school building, in itself a masterpiece of Bauhaus modernism. ‘The majority of the products and buildings that still defined the image of the Bauhaus today were created in Dessau. In Dessau, the stylistically influential use of lower case lettering was established for the first time, and the foundation of the company Bauhaus GmbH allowed the students to participate in the success of the products developed at the Bauhaus.’i

The paradox of the early Bauhaus was that although its manifesto proclaimed that the aim of all creative activity was building the school did not offer classes in architecture until 1927.

In 1928 the architect Hannes Meyer replaced Gropius as director of the school. In 1930, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, also an architect, replaced Meyer as the school moved to Berlin. He reconfigured the curriculum, shutting down the school’s manufacturing activities and placed an increased emphasis on architecture. The increasingly unstable political situation in Germany, combined with its perilous financial conditions was the ultimate cause of the Bauhaus school’s closure in 1933.

The Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany; image taken in 2003. Photo courtesy of Mewes.

“The most important design principle of the Bauhaus school was the emphasis on an object’s function defining its form.”

Frank Bauer, Three Stirling Silver Bracelets, 1995. Photo courtesy of the artist.

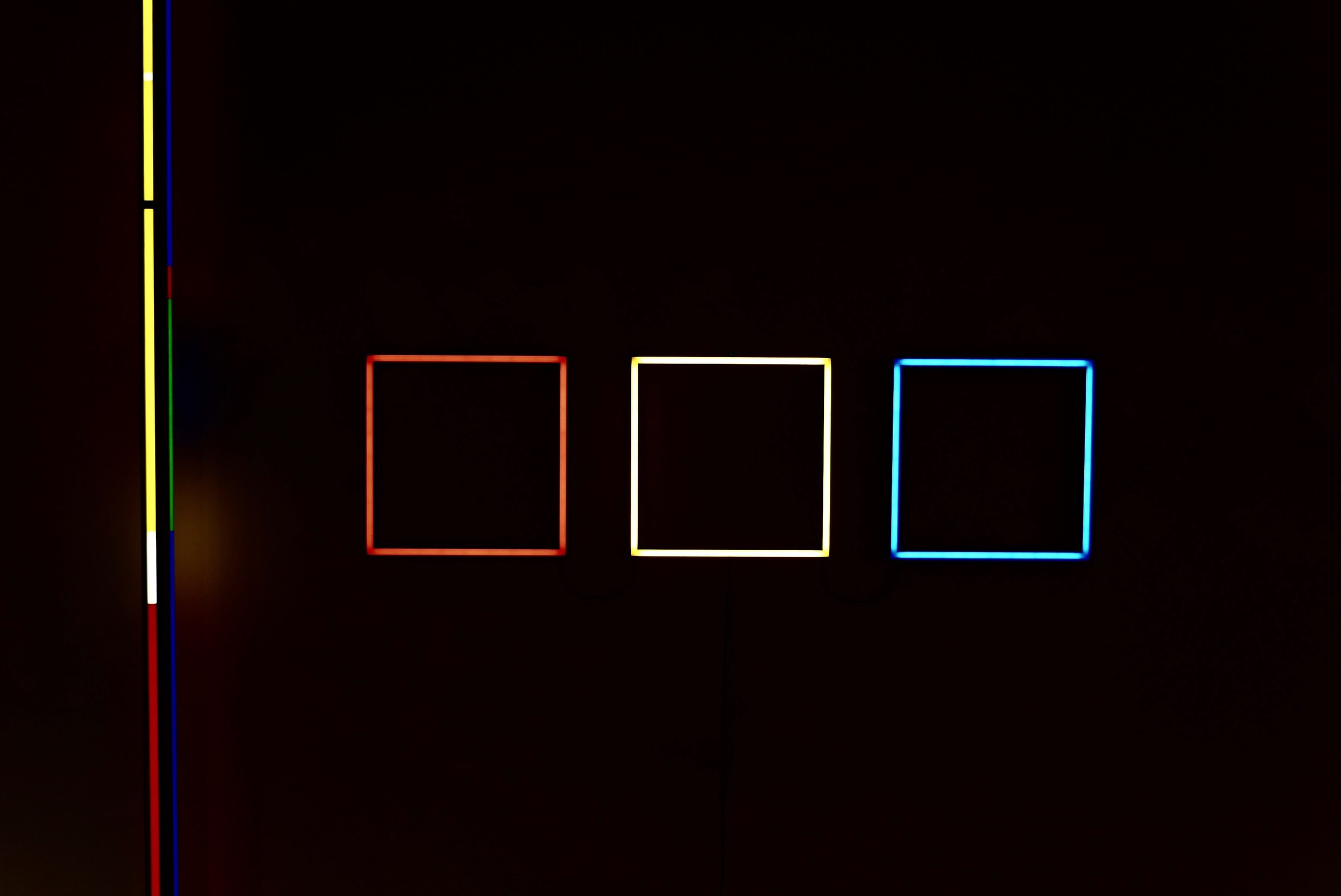

Frank Bauer, Three LED squares, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

BAUER HAUS

During the turbulent years of World War II, many of the key figures of the Bauhaus emigrated outside of Germany, primarily to the United States, where their work and teaching philosophies influenced generations of young architects and designers. In Australia, the influence of Bauhaus was spread most notably through émigré artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and Austrian-born Australian architect Harry Seidler. A founding member of the Weimar Bauhaus, Hirschfeld-Mack introduced Bauhaus methods into Australian art education while producing a substantial body of his own work over three decades. Seidler, a consummate modernist, was taught by émigré instructors: Walter Gropius, Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer at Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1945-46. He subsequently introduced Bauhaus methodology to Australian architecture.

Metalsmith, lighting sculptor and kinetic artist Frank Bauer also has a direct lineage to the Bauhaus school. His father Carl Bauer trained as an architect at the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin. Frank grew up in post-war Germany where he was raised on the philosophy that art, design and industry could work together to achieve a more visually coherent and democratic society. He describes it in his standard Germanic figuration as, ‘you start to walk on two-feet because you see your parents walk on two-feet.’ While there are architectural testimonies in Frank’s designs, he did not follow the career path of his father. Rather the school’s ideals in applied art, design, craft and metal manufacturing became his central interests. Bauer’s series of hinged and folding bracelets, Three Sterling Silver Bracelets, 1995 can be worn in multiple configurations. They are scaled down versions of sculptures made by Bauer during his time in one of JamFactory’s tenanted studios in the mid-1970s,

The most important design principle of the Bauhaus school was the emphasis on an object’s function defining its form. From the strict geometry of his jewellery to his pure enjoyment of red, blue and yellow in his primary-coloured light sculptures, Three LED squares, 2014 and LED Light column, 2013, Bauer’s design aesthetic unites this principle in the most elegant of solutions. Testament to Bauer’s modernist heredity and mastery of metals is the inclusion of his works in the collection of the Bauhaus Archiv, Berlin.

PROTOTYPES FOR INDUSTRY

Furniture designer Lex Stobie exemplifies the universal Bauhaus ‘artist-craftsman’. The clean lines, pared back aesthetic, pronounced joinery and honesty to materials of Stobie’s wooden furniture demonstrates a Scandinavian sensibility. The minimalism and functionalism that Bauhaus espoused was prevalent in the aesthetics fused with efficiency of mid-century Scandinavian design. Originally designed as a commission for the Sydney Opera House, Stobie’s Halo stool, 2017, is synonymous with the design-led prototypes for industrial production conceived by the Bauhaus.

‘Bauhaus workshops are laboratories in which prototypes of products suitable for mass production are carefully developed and continually improved,’ declared Gropius in his 1919 manifesto. ‘In these laboratories, the Bauhaus will train and educate a new type of worker for craft and industry, who has an equal command of both technology and form.’ii

“…the Bauhaus will train and educate a new type of worker for craft and industry, who has an equal command of both technology and form.”

Lex Stobie, Halo Stool, 2015. Image courtesy of the artist.

Liam Fleming, Graft Vase, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

COLOUR THEORIES

The varying modulations of Liam Fleming’s press moulded Graft Vases, 2019 draws on the colour theories of Bauhaus faculty members and painters, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. Fleming’s multiple cubic glass forms in varying sizes and colours reference the intersection of glass, colour and music. Like Kandinsky and Klee, Fleming sees colour and form in musical terms, making the connection between lofty, harmonious sounds and complementary colours, as well as at, dissonant sounds with colours that clash. The juxtaposition of line and colour results in a sense of musical rhythm connecting the repetitive tempo of the glassblowing process. The stainless steel sculptural work of Bauhaus student Heinrich Neugeboren should also be noted in relation to Fleming’s practice. Sculptural Representation of Bars 52-44 of Eb Minor, 1928 is Neugeboren’s visual representation of part of a Bach fugue.

Ceramic artist Susan Frost’s geometrically patterned porcelain vessels, made in a spectrum of hues are characteristic of the colour theories that were critical to the school and a mandatory part of the preliminary course. Josef Albers, a painter, designer and educator taught the preliminary course at the Bauhaus from 1923-1933. He noted that the perception of colour is always relative and subjective and that the relationship between colours could alter what we see.iii

In Yellow to Blue, 2018, Frost’s light yellow vessel, for example, looks completely different from the same yellow in a sea of blue.

Exhibitors Kay Lawrence and Gabriella Bisetto represent the current faculty at the School of Art, Architecture and Design at the University of South Australia (UniSA). Lawrence, formerly the Head of the South Australian School of Art, is an Emeritus Professor and supervisor to PhD project and Masters research students in Visual Art and Design whilst Bisetto is a Senior Lecturer and Head of the Glass Workshop. Bisetto employs the principles of Itten’s preliminary course in her teaching methods as well as in her conceptual artworks and functional glass designs.

The sculptural pendant light series Umbra, Eclipse and Helion, 2019 are collaborative works made by Gabriella Bisetto with her partner and fellow glass artists Chris Boha, as Boto Design. In these pendants Bisetto and Boha investigate the relationship between colours, and their different modes of contrast through carefully considered balance, harmony and proportion of their simplified, functional forms.

It should also be noted, that Frost and Boto Design apply the principle of ‘stacking’ within their forms. The aesthetic styling and colour design utilised in Boto’s designed lights and Frost’s nest of bowls is familiar to Marcel Breuer’s Stacking Tables, 1925.

FEMALE BAUHAUS

‘Any person of good repute, without regard to age or sex, whose previous education is deemed adequate by the Council of Masters, will be admitted, as far as space permits,’ wrote Gropius in his Programme of the Staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar, a manifesto of sorts outlining the guiding principles of the school in 1919. However, ‘as early as September 1920, Gropius was suggesting to the Council of Masters that “selection should be more rigorous right from the start, particularly in case of the female sex, already over-represented in terms of numbers”. He further recommended that the “unnecessary experiments” should be made, and that women should be sent directly from the Vorkurs to the weaving workshop, with pottery and book binding as possible alternatives.’iv

By contrast, by the 1970s during the foundation of JamFactory in South Australia, there was a shift from male-dominated practice with the entry of more women into both craft and design as artists, curators and teachers.v Despite its limitations, nascent textile artists like Anni Albers and Gunta Stotzl not only advanced the Bauhaus school’s historic marriage of art and function; they also laid the groundwork for centuries of art and design innovation to come after them. Stotzl used the workshops to appropriate new unorthodox materials like cellophane and breglass in her practice, whilst Albers became the rst woman at the Bauhaus to assume a leadership role when she was appointed the head of the weaving workshop in 1931.

In Materials Matter, textile artist Kay Lawrence revisits her series of tapestried tea towels from 2009 to reveal a compelling new narrative in Lineage, 2009-19. Viewed in this exhibition’s context the Bauhaus-esque simple stripes and checks interweaves the experiences and artistic legacies of the long overshadowed women at the Bauhaus. ‘My life has had opportunities unimaginable to young women coming to maturity in the early years of the 20th century,’ Lawrence re ects. One hundred years later women can experiment in new ways and in elds that previously would not have been at their artistic disposal. These weavings, which are inherently geometric in their design represent a continuity of technical aspects that honour and evoke the artistic practices of women like Albers and Stotzl.

Emerging textile artist Lilly Buttrose’s collaboration with furniture designer Matthew Taylor in the creation of Horizon, 2017 recalls the creative partnerships of the Bauhaus, like

that between Gunta Stotzl and Marcel Breuer. Informed by Buttrose’s residency in Itoshima, Japan, Horizon is a reimagining of the traditional Japanese changing screen and captures the unique relationship between mountain and sky. Like The Africa Chair, 1921 by Stotzl and Breuer, Horizon reflects an artistic interest in the visual qualities of hand-crafted non-Western ethnographic design.

Buttrose’s recent work Momentum, 2019 continues her experiments with embroidered landscape on fabric. The imagery of a cityscape at night has been reduced to its basic geometric lines. Just as a century ago artists and makers looked at how to live in a world altered by industrialisation - Momentum summons questions surrounding cultural modernity in a globalised, digital age.

“As a designer/maker it seems so important to use materials as thoughtfully and as economically as we can”

Lilly Buttrose, Horizon, 2017 and Momentum, 2019. Image courtesy of JamFactory.

Lilly Buttrose, Momentum ( detail), 2019. Image courtesy of JamFactory.

Ebony Heidenreich, Poolside, 2019. Image courtesy of JamFactory.

Jake Rollins, GolfWeave, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

ECOLOGICAL DESIGN

Metal designer and maker Christian Hall’s series Stratigraphic Studies, 2019 embodies his recent investigations into the interrelationship of the artist, the landscape and the studio-based practice of the designer.

The pressed steel rings, stacked and connected via molten welds display the time and process of hand-making, and were made in response to Hall’s recent eldwork in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia. These works also capture the essence of Bauhaus metal workshop professor Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s functionalist philosophies that looked to “nature as a constructional model.” This interest in using nature and science to improve architectural design grew exponentially during the little studied interlude of the Bauhaus in 1930s London. During this period, former faculty members including Walter Gropius and Herbert Bayer as well as Moholy-Nagy began working closely with leading British ecologists. The ‘London Bauhaus’ was short-lived but showed early signs of a growing need for -environmental sensitivity.

The works of emerging designers Jake Rollins and Ebony Heidenreich speculate on how the ideas and themes of the Bauhaus will stimulate the next 100 years of craft and design. Their works address the new challenges of material culture through a strong focus on functionalism, sustainability and regeneration.

Ceramic artist, Heidenreich’s designs originate in the Bauhaus thesis, allied with the constructivists, of a reduction of form to primarily three simple geometric shapes: pyramid, cube, and sphere.

Poolside, 2019 takes inspiration from the at, concrete textures and cubic forms preferred in Bauhaus architecture. Its clean white surface enhances the interplay of light and shadow and pays homage to the White City architecture constructed by German Jewish émigré architects in Tel Aviv in the 1930s.

Heidenreich’s works also provide new insights into the evolution of environmental awareness and sustainable practices. While in the early 20th century there was no talk of sustainability, from a conceptual standpoint, minimalist design is by its very de nition favourable to sustainability.

The economy of Heidenreich’s designs as well as her conglomeration of clay off cuts, essentially waste products, show a ‘Bauhausian’ honesty to materials. ‘As a designer/maker it seems so important to use materials as thoughtfully and as economically as we can,’ she asserts.

Jake Rollins building block concept applied to his GolfWeave, 2019 has an almost limitless variety of con gurations. A snip to its single length of cord can return the object to its raw materials to be repurposed again. In his structure Rollins utilises ‘paddock balls’– golf balls recovered from dams and streams that would otherwise become villains in the modern waste crisis.

The Bauhaus experimented with materials and form, creating design that was unprecedented in its clarity and functionality. Materials Matter highlights how artist, designers and makers have adapted its legacy for contemporary purposes to ensure these principles live on.

Put simply, without the Bauhaus, JamFactory as we know it would not exist. In the words of Frank Bauer ‘... [we are] just part of a long, continuous chain, with a long accumulation of techniques and wisdom. We are always constantly building on that, and we should acknowledge that. We should give homage to predecessors.’

i https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/phases/bauhaus-dessau/

ii Walter Gropius quoted in ‘Principles of Bauhaus production’ in Conrads, Ulrich, Programs and Manifestoes on 20th century Architecture. First published 1964, Updated 1971, MIT Press

iii Albers, Josef, Interaction of Colour, First published in 1963, Updated in 2013, Yale University Press

iv Droste. Magdalena, Bauhaus 1919- 1933, 100 years of Bauhaus, First published 1990, Updated 2019, Bauhaus-Archiv/Museum fur Gestaltung in Berli and Taschen v Richards, Dick and Ian Were, Designing Craft/Crafting Design: 40 Years of Jam- Factory, 2013, JamFactory Contemporary Craft & Design.

Materials Matter: A Bauhaus Legacy is exhibiting at JamFactory Adelaide in Gallery One until 13 July 2019.

Curators:

Rebecca Freezer and Margaret Hancock Davis

Essay:

Rebecca Freezer

Exhibitors:

Frank Bauer

Gabriella Bisetto

Lilly Buttrose

Liam Fleming

Susan Frost

Christian Hall

Ebony Heidenreich

Kay Lawrence

Jake Rollins

Lex Stobie